|

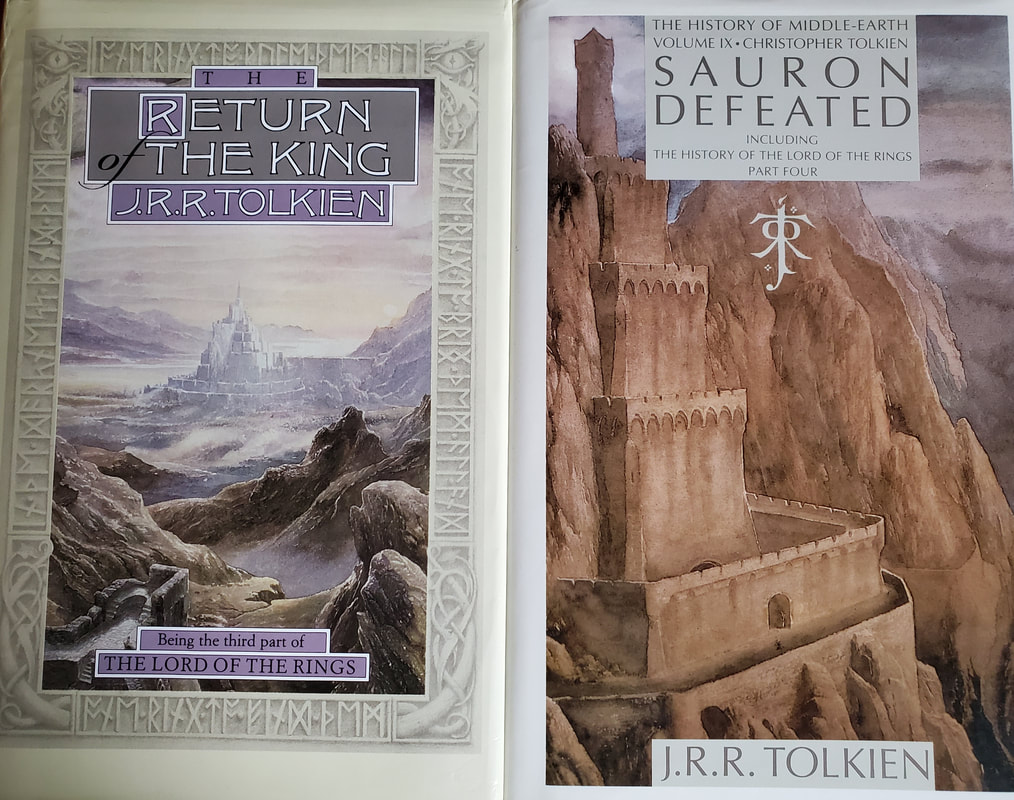

Rather long post, just saying. ‘Do what?’ said Pippin. ‘Raise the Shire!’ said Merry. (RK p. 286) For Tolkien reading day 2020 ‘The Scouring of the Shire’ was one of the Tolkien Society’s suggestions for the theme “Nature and Industry”. I decided to read ‘Homeward Bound’ and ‘The Scouring of the Shire.’ I’ve always found ‘The Scouring of the Shire’ to be one of my favorite chapters in The Lord of the Rings (LoTR), but I hadn’t really dug into it too deeply. I included ‘Homeward Bound’, because I saw this chapter as foreshadowing much of what was to come. In addition to the Return of the King (RK) versions, I also read the History of Middle Earth (HoME) versions, and searched for references in Shippey’s Author of the Century (AC) and Road to Middle Earth (RME). To warm-up, I read several blog posts on the ‘Scouring of the Shire’. Each one focused on either Tolkien’s experience in the war and returning from war or it was about the rise of industrialization, which was counter to Tolkien’s love of the countryside and trees or both.

Attributing Tolkien’s experience to the LoTR is commonly done and something that Tolkien did not care for, but he did not completely deny. Shippey wrote, “‘The Scouring of the Shire’ had ‘some basis in experience’ though no ‘contemporary political reference whatsoever,’ not even to Britain’s Socialist ‘austerity’ government of 1945-1950.” (RME p. 169). The basis was more likely from Tolkien’s childhood, “when places like his old home in Sarehole, Warwickshire, were being drawn into the industrial Birmingham conurbation.” (AC p. 167). A few addressed the chapter as the true coming of age moment for the four hobbits. This is how I had previously taken this chapter. It was the ‘culmination’ of their experience. Everything they had encountered and learned was now put toward doing good in their own community and setting the course for their individual futures. “At last the hobbits had their faces turned towards home. They were eager now to see the Shire again; but at first they rode only slowly, for Frodo had been ill at ease.” (RK p. 268) Frodo was on the anniversary of his wound and nearing the site of it. He speaks with Gandalf who has continued journeying with them as all the others have gone their own way. “‘Alas! There are some wounds that cannot be wholly cured,’ said Gandalf. ‘I fear it may be so with mine,’ said Frodo. ‘There is no real going back. Though I may come to the Shire, it will not seem the same; for I shall not be the same.’” (RK p. 268) While the dialogue is specific to Gandalf and Frodo, I take this passage with a larger meaning. As the ring-bearer, Frodo, may be the most impacted, but Sam, Merry and Pippin will also never be the same as a result of their experience on this journey. ‘Homeward Bound’ covers the journey from east of Weathertop to the departure of Gandalf to visit Tom Bombadil. At Bree, the party finds the gate shut and not wanting outsiders. Arriving at the Prancing Pony, Butterbur welcomes them and they learn things are not well in Bree and he eventually tells them the same is true of the Shire. In their discussion with Butterbur and again in their time in the Common Room the next day, the hobbits all take note that the great events away south are of little to no interest to the people and that they have hardly any knowledge of what has been transpiring. With the understanding of all that has happened, the hobbits find this hard to believe. Having been so integral in the events, Frodo’s words were beginning to ring true. The Shire will not seem the same as it had, nor will the four hobbits to all they encounter and had known them before. “The four hobbits like riders upon errantry out of almost forgotten tales” (RK p. 274). Upon their departure as Butterbur reluctantly tells them all is not well in the Shire, he also tells them that from the changes in them that he has seen, he believes they will take care of themselves and set things right. As they ride toward the Shire, Sam recalls the memory of the image he saw in Galadriel’s mirror. Pippin lays the blame on Lotho, but Gandalf reminds the hobbits, “You have forgotten Saruman. He began to take an interest in the Shire before Mordor did” (RK p. 275). In an earlier version, Gandalf does not mention Saruman. Had the hobbits been confronted with Lotho, as opposed to Saruman, the stakes would not have been so high. Lotho was an equal as a hobbit, whereas Saruman was the head of the White Council. While Lotho felt cheated by Frodo for becoming Bilbo’s heir, Saruman felt cheated by Frodo for having denied him the One Ring and ability to rule over all. Gandalf then tells the hobbits he won’t be joining them on their final journey to the Shire. He intends to sit down and have a long talk with Tom Bombadil. He goes on to tell them that they have grown up and been trained for what lies ahead. They are ready and he is done helping and righting ways. Again, the earlier version has Gandalf going with the hobbits to the Shire, but his being present and serving a role in the scouring would prevent the hobbits from ‘completing’ their journey and coming into their own. “‘Well here we are, just the four of us that started out together,’ said Merry.” (RK p. 276). This was very near the end of ‘Homeward Bound’, and as I considered this chapter, Merry’s words could have made for a decent ending. Decent, but still wanting. ‘Homeward Bound’ in foreshadowing some of the events to come begins to draw the distinction between the Shire then and now, as well as the hobbits. The Shire has changed, not for the better, but the reader does not know the extent and the hobbits have changed, as the reader is reminded through the perspective of the others in Bree and Gandalf himself. Returning home demonstrates how changed the four hobbits, the travellers, have each become and in their own way, as well as how the bigger events that have transpired impacted the Shire. At the same time, it reinforces the shire-folks’ concern for local affairs without regard to the bigger ones. Finally, as the travellers have changed, so too has Saruman. Similar to their arrival at Bree, the four hobbits come at night. It is damp and cold. They are tired. They find a gate on both ends of the Brandywine bridge where there hadn’t been ones before. They also notice new, un-hobbitlike, buildings on the far side of the river. After some time they are told to go away and to read the notice on the gate, which in the dark they don’t see. Merry recognizes a hobbit, Hob Hayward, and addresses him. They learn the “Chief” is at Bag-End. Frodo assumes it is Lotho despite Gandalf’s warning of Saruman (RK p. 277). When entrance continues to be denied, it is Merry who takes action, calling Pippin to join him; they climb the gate and enter. Then one of the ruffians, big men, arrives. It is Bill Ferny from Bree. At first, he is confident of bullying the little people, until he catches the glint of the swords held by Merry and Pippin. Merry addresses him by name, commands him to open the gate, and tells him to leave and never return, which he does. In this scene, Merry is truly an adult hobbit. Moreso, he is battle hardened and has taken the lead. It is also noted a few pages later that they (Merry and Pippin) are “uncommonly large and strong-looking” (RK p. 279). So, thanks to the Ent draught they have significantly physically changed, too, especially in the eyes of their fellow hobbits. Many of the lines and actions attributed to Merry in these early passages were originally spoken by Frodo or Gandalf. The removal of Gandalf allows for the development of the hobbits. Frodo, though, is at first an aggressive leader in the early versions of this chapter. Through revision, he becomes more thoughtful and ultimately pacifist. His role is more of adviser and protector of all, while the others remind him that fighting will be inevitable under the current conditions. Within the gates, the four learn the inns have all been closed, food and wood for fire is rationed, and there are many rules to follow. The rationing is based on the sharing and gathering, or more to the point the gathering without sharing done by the men at the expense of the hobbits. The expansion of rules leads to the need for enforcement and to that end more and more hobbits are enlisted to serve as Shirriffs. On the main road, heading to Frogmorton, they encounter a band of Shirriffs who are there to arrest them. In this scene, Frodo is “inclined to laugh” (RK p. 280) and asks what is going on? Being told the four are being arrested and read the charges, Frodo asks, “And what else?” Sam speaks up next and the Shirriff responds, resulting in laughter from the four. Frodo then replies, “I am going where I please, and in my own time. I happen to be going to Bag End on business, but if you insist on going too, well that is your affair.’” (RK p. 280). He then says shortly after being told not to forget he has been arrested, “Never. But I may forgive you.” This is the last instance in the final version that Frodo acts in this manner. The more he sees, the more he is saddened. The next day the arrested hobbits head out to Bag-End on their ponies. Merry has the Shirriffs lead the way as “Merry, Pippin, and Sam sat at their ease laughing and talking and singing, while the Shirriffs stumped along trying to look stern and important. Frodo, however, was silent and looked rather sad and thoughtful.” (RK p. 282) Originally, it was Frodo who drove the Shirriffs, so this is truly the turning point in the direction Frodo would take through this chapter and those remaining. As Merry continues to take the lead in the final version, Frodo becomes more resigned and thoughtful than he had been. Frodo is the first of the four to be thinking about the macro aspects of what is happening in the Shire, while the others are focused on the micro ones. Part of this could be attributed to age, Frodo is older than the others, and he also has had more ‘bigger’ discussions than the others, particularly with Gandalf, through the years. The driving of the hobbit Sherriffs, some who enjoy their role and many more who do not, but don’t know how to get out of it, points out the division created of hobbit vs. hobbit, which is a likely potential source of Frodo’s sadness. Arriving at Bywater, “they had their first really painful shock. This was Frodo and Sam’s own country, and they found out now that they cared about it more than any other place in the world.” (RK p. 283). Homes were missing, some burned down, trees were gone, and ugly houses were erected. In the distance a tall chimney of brick blew black smoke into the sky from the area of Bag End. At the Green Dragon, the hobbits encounter a half dozen ruffians. Merry toys with them in his responses before aggravating them. At that point Frodo speaks up ‘quietly’. Frodo attempts to talk through things with the ruffian. When told Saruman is a ‘beggar in the wilderness’, the ruffian becomes very direct with Frodo, insulting him. It is too much for Pippin. Pippin, the youngest of the four and possibly still the most apt to act before thinking, throws off his cloak declaring, “I am a messenger of the king,’ he said. ‘You are speaking to the King’s friend, and one of the most renowned in all the lands of the West. You are a ruffian and a fool. Down on your knees in the road and ask pardon, or I will set this troll’s bane in you!” (RK p. 285) Merry and Sam drew their swords and stood alongside Pippin. The ruffians turned and fled. It is at this point that Frodo explains to Pippin and the others how he believes things have transpired in the Shire regarding Lotho, the bringing in of the ruffians, and the trap Lotho has now found himself in. Pippin is incredulous that after everything they return to the Shire to save Lotho. “Of all the ends to our journey that is the very last I should have thought of: to have to fight half-orcs and ruffians in the Shire itself - to rescue Lotho Pimple!” (RK p. 285). Frodo considers fighting and acknowledges it may come to that, but killing must be avoided. Merry and Pippin impress upon Frodo that they may have scared the ruffians in small numbers, but it won’t happen again and they will come with greater numbers and be better prepared. Frodo seeks a peaceful way to resolve the current state of the Shire and return it to what it once was, but Merry and Pippin are more realistic given the situation. Sam suggests going to Tom Cotton’s. At this point, the four have mostly shown who they have become. One way of highlighting this is by considering them opposite another from this chapter. As Tolkien seems to take to pairings, such as orcs and elves and trolls and Ents, I tried to consider the opposite pairings in this chapter: Saruman and Frodo, Wormtongue and Sam, Bill Ferny and Merry, and Ted Sandyman and Pippin. Saruman becomes corrupted in his desire for power and seeks it through the Ring. Frodo is a reluctant leader, who by virtue of being possessor of the Ring, feels obligated to be the Ring-bearer and destroy it. By doing so it breaks him as well. Having lost most of his power, Isengard, and being left with his voice and Wormtongue, Saruman seeks revenge on the hobbits by destroying the Shire. The hobbits meeting Saruman on the road only strengthens his resolve. Despite the damage he has done, Frodo does not wish him death. In frustration Saruman stabs Frodo. Again, Frodo calls off the hobbits from harming Saruman. When Saruman begins to leave, Frodo offers Wormtongue to stay, eat and rest as he has done nothing to Frodo. Now, Saruman sees the last thing he has in danger of being taken away from him, too. He tells of Wormtongue murdering Lotho in his sleep, kicks him and demands him to follow, at which point Wormtongue pulls a knife, kills his master and is shot by hobbits before Frodo can stop them. Frodo shows himself full of mercy and Saruman the opposite. Both Wormtongue and Sam are loyal to their respective masters, but for very different reasons. Wormtongue was loyal to Saruman for power of his own. He didn’t need dominion over all, but he did want power that he could wield over others and Saruman was his means to that end. Sam was loyal to his master out of respect and love. Early on, Sam is depicted akin to a loyal dog at his master’s feet. He grows into a faithful servant who is willing to put his own life on the line for his master to gain nothing for himself except personal satisfaction. Merry throughout is more thoughtful and a bit more reserved than the more spontaneous Pippin. This could be chalked up to maturity, but it is also a difference in personality and character. Merry breaks orders for the purpose of ‘doing his part’ as every other race was doing. He suffers great pain in stabbing the Witch-King. In the Shire he takes the lead and seems to intuitively understand what needs to be done. On the other hand, Bill Ferny, a big person, is thoughtful, but only in a way that benefits himself. He does read situations, but does so for self-preservation. This is most obvious when he goes from being a ruffian to fleeing the Shire upon seeing the swords of Merry and Pippin. Pippin, as mentioned, is the youngest of the four hobbits, and often acts impulsively and isn’t always so aware of what is happening on a larger scale - he just wants to be a part of it. He is the most carefree of the four. Ted Sandyman, a hobbit, thinks he is aware of what is happening on a larger scale, but really doesn’t. He feels good about himself when others are down or put down. The remainder of the chapters solidify how they will be remembered based on their deeds in the Shire itself, with those acts outside of it barely known in the Shire, but honored throughout the West. Beyond character development, though, there is something more in this chapter. To Sam’s suggestion of going to Farmer Cotton’s, Merry replies, “No! It’s no good ‘getting under cover’. That is just what people have been doing, and just what these ruffians like. They will simply come down on us in force, corner us, and then drive us out, or burn us in. No, we have got to do something at once.’ ‘Do what?’ said Pippin. ‘Raise the Shire!’ said Merry.” (RK p. 286) This is what I missed when I only thought of this chapter in terms of the characters coming of age. The real significance was addressed by Tom Shippey in J.R.R. Tolkien: Author of the Century (AC p. 219, 220) as he explains how the rebellion in the Shire begins when Merry blows the Horn of Eorl the Young, given to him by Eowyn. When sounded, the hobbits’ paralysis dissipates and everyone seems to wake up. Shippey calls it a rejection of despair. He goes on to say: “If Tolkien were to choose a symbol for his story and its message, it would be, I think, the horn of Eorl. He would have liked to blow it in his own country, and disperse the cloud of post-war and post-faith disillusionment, depression, acquiescence, which so strangely (and twice in his lifetime) followed on victory. And perhaps he did.” (AC p. 220, 221). Destroying the Ring stopped Sauron and it was a victory in preventing further loss, but the true victory is revealed in rejecting the despair felt by all who live through such times. It is not the point of feeling relief that things won’t get worse, it is the lifting of despair knowing and believing that things will be better. The raising of the Shire was the rejection of despair. The hobbits, together, could and would take action to be independant once again. In closing, is ‘the Scouring of the Shire’ about nature and industry? Kind of, but not really. It is included to highlight how the four hobbits have grown individually and most importantly, it demonstrates the power of unity and rejecting despair. Comments are closed.

|

AuthorRoss R. Nunamaker Archives

July 2023

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed